Then also how intense and concentrated he might be, and at the same time, self-reflective, thinking about his own experiences and the words he was using to describe them as he was saying them, as he was talking to you.

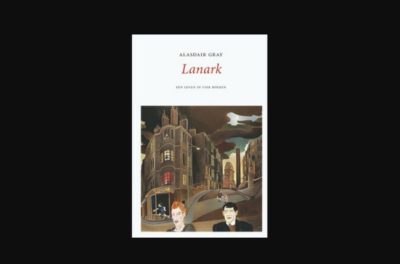

How his voice worked, how sometimes something would trigger a wild guffaw and paragraph after paragraph of unpredicted verbal extrapolation, exhilaration, exaggeration, arms moving in all sorts of directions. How his eyes would move from object to object, or look at you with curiosity and penetration, defensive yet open, curious yet respectful. I’ve been thinking about Alasdair’s hands, how he would handle things like pens, brushes, books and easels, how the touch of his fingertips and the hold of his fingers enabled the contact between pages and eyes and minds, between what ink is made of and the phenomena of words, how language works in writing and in speech. I’ve been wondering about Lanark as the work of a physical human being, a man, about how it was thought of, imagined and planned, and then how it was made, literally, written with paper and ink and pens, leaning on a desk, and its transformation and creation as a book, published, launched at an event, and bought and taken away and read by other individual human beings, women and men, in the forty years between then and now. 25th February 2021 is the first GRAY DAY, a celebration of the writer and artist ALASDAIR GRAY, on the 40th anniversary of his masterpiece Lanark. A guest blog by Alan Riach, Professor of Scottish Literature, University of Glasgow.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)